Precinct Voting is Key to Election Integrity: Structural Risks in Vote Centers, Central Count, and the Case for Precinct Voting

Executive Summary

Central voting and tabulation centers are a lynch pin of election vulnerabilities: a return to precinct voting is essential to resolving one of the greatest threats to the integrity and accuracy of our elections.

Modern American election administration has quietly shifted from a dispersed, precinct-based model toward a highly centralized architecture built around large vote centers, ballot on demand, central absentee counting facilities, and county-level tabulation hubs. This concentration of critical functions has made central voting and tabulation centers the lynch-pin of contemporary vulnerabilities: these hubs are easily susceptible to being misconfigured, compromised, or simply overwhelmed, and the absence of designated locations and venues for voting makes it impossible for election officials to properly plan for and track the voters and their votes. As a consequence, the integrity and public credibility of the entire election is placed at risk.

The 2020 presidential election in Georgia, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Arizona relied heavily on centralized structures not only for voting but also to manage and process unprecedented volumes of mail and early voting. Multiple reviews since 2020 and subsequent disclosures have documented procedural flaws and documentation failures in central-count operations, underscoring that the absence of overturned results is not the same thing as a clean bill of health for the underlying processes.

Although vote centers are marketed as a means of increasing turnout through convenience, research indicates mixed and often unequal effects on participation, especially where consolidation increases distance and complexity for less-resourced voters, while simultaneously increasing the security and transparency risks of voting centralization. This paper argues that a more resilient architecture is possible—one that restores precinct-level voting as envisioned in election codes across the nation, allowing for pre-election planning and certainty of the eligibility of voters in the precinct, pre-printing of correct numbers of ballots, on hand-marked (and, if needed, hand counting) of paper ballots, and reduces dependence on complex, centralized electronic systems that are costly to procure and operate, and impossible to secure.

Central tabulation centers and vote centers: what they are and why they are wrong for elections

Vote centers are large, often countywide locations where any eligible voter in the jurisdiction can cast a ballot, replacing or sharply reducing the number of neighborhood precincts. Vote centers are frequently paired with electronic pollbooks and high-capacity voting equipment, and are promoted as a method to reduce costs, simplify logistics, and give voters more flexibility in where they vote. In practice, this architecture shifts election administration away from a network of many small nodes toward a smaller number of large hubs, with significant implications for security, transparency, and operational risk.

Central tabulation centers are county or jurisdiction-level facilities where results from optical scanners and central-count systems are aggregated into unofficial and then official totals. In many jurisdictions, the same or adjacent facilities also host the central processing of mail and absentee ballots, including signature verification, batching, scanning, and adjudication of ballots flagged by scanners.

Why Vote Centers and Central Tabulation Create Distinct Vulnerabilities

As election administration has shifted toward consolidation, two distinct systems—vote centers and central tabulation centers—have emerged as defining features of modern elections. Each introduces its own vulnerabilities that undermine transparency, accountability, and ultimately public confidence. Understanding these weaknesses separately helps clarify why precinct‑level voting and counting remain the foundation of electoral integrity.

First, vote centers are often promoted as a modern and convenient alternative to neighborhood polling places. Supporters claim they reduce costs, streamline logistics, and make voting more flexible by allowing any eligible voter to cast a ballot at any county location. In reality, these large, technology‑driven hubs create more risks than benefits. Because vote centers must manage huge volumes of voters using county‑wide electronic pollbooks, they depend on complex networks and real‑time data synchronization across multiple sites, so a single software error or communication failure can ripple across every location. At the same time, large‑scale operations erode the human‑scale protection of local familiarity that smaller precincts once provided; poll workers rarely recognize voters personally, making it harder to catch duplicate registrations, address mismatches, or unusual patterns in real time.

Placement and consolidation decisions add another, more troubling layer. Consolidation when counties close many neighborhood precincts and replace them with a smaller number of vote centers, where those centers are placed becomes a quiet but powerful way to shape who can realistically participate. Locating more sites in some areas may disproportionately suppress the vote of specific demographics and may increase the cost of voting for some groups while lowering it for others, with predictable effects on turnout and representation. Since placement of vote centers cannot be objectively guaranteed voters may not receive fair and equal access to a polling location.

Vote centers also require co‑mingling of ballots from across an entire county. This further complicates any serious effort to audit or reconstruct what happened in a given election. When ballots are issued and cast in locations that serve all precincts, and then are stored and processed without preserving clear precinct‑level separation, it becomes difficult or impossible to trace results back to specific neighborhoods and precincts. This loss of delineation undermines one of the most powerful checks in a precinct‑based system: the ability to compare reported results with expected patterns and turnout in each precinct, and to “reverse engineer” an election by re‑examining ballots and records within well‑defined geographic and administrative boundaries.

Observation also suffers in vote‑center environments. These locations reduce the kind of close, end‑to‑end transparency that lets citizens watch every step of check‑in, ballot issuance, and reconciliation. Voters and observers see only fragments of what is happening, while crucial decisions about how electronic pollbooks are configured and updated, how provisional ballots are handled, and how volumes are managed occur within software and workflows that are difficult for outsiders to inspect. This combination of technological complexity, high volume, and demographically skewed placement means that vote centers can change who votes, how easy it is for them to do so, and how much of the process anyone outside the administration can observe.

Central tabulation centers present a different kind of vulnerability: one tied to the processing of final results. These facilities have become the ultimate convergence point for vote aggregation and reporting, turning them into true single points of failure. Every result file, memory card, or scanner report flows through the same handful of servers and databases, so a single configuration error, software glitch, or insider mistake can create wide‑scale disruptions or reporting anomalies that, even when later corrected, damage trust in the outcome. Because most tabulation environments operate behind closed doors with limited observer capacity, irregularities tend to surface through leaks, litigation, or post‑hoc reviews rather than through real‑time public visibility. Although officials often assure the public that these systems are “air‑gapped,” security assessments insist that some use internal modems or other forms of connectivity that fall short of strict isolation, introducing exactly the network risks those assurances are meant to deny.

Both developments—expansion of large vote centers and reliance on centralized tabulation—reflect a gradual substitution of technology and administrative efficiency for transparency, local engagement, and equal access. Consolidation can make management easier for administrators, but it makes the system harder for citizens to observe, more difficult for some voters than others, and more fragile when something goes wrong. By contrast, precinct‑level voting and tabulation distribute responsibility and risk across many small precincts rather than concentrating them in a few powerful hubs. In a precinct‑based system, each location maintains a bounded list of voters, conducts its own ballot reconciliation, and posts results that can be publicly viewed and verified before aggregation, so problems or discrepancies remain local and containable. Most importantly, precinct‑scale operations preserve human oversight that technology cannot replace citizens working in their own communities, knowing their neighbors, and seeing the process from start to finish.

Restoring the emphasis on precinct‑level voting and in‑precinct tabulation does not reject modernization; it restores proportion and balance. Technology should serve the people, not obscure their access to oversight. By keeping voting, counting, and verification close to the voters themselves—and by avoiding placement decisions that quietly shift costs onto specific communities—election systems regain both accuracy and the public confidence that comes only from visibility, fairness, and shared responsibility.

Precinct-scale vetting versus jurisdiction-wide electronic pollbooks

The key component and argument in favor of precinct voting is the ability of election officials to conduct pre-election voter-eligibility vetting and qualified voter lists and management. Traditional precinct-based systems operate at a human scale: each precinct has a bounded list of eligible voters, and poll workers often develop familiarity with local patterns and voter identity over time. This structure makes it easier to notice irregularities, resolve address questions, and reconcile lists in a transparent end-of-day process. It is also easier and more convenient for voters to travel to precinct polling places rather than areawide vote centers, which are often located miles from voter residences and which locations may be subject to manipulation for partisan purposes. For instance, it has been documented that in Maricopa County in elections since 2020 that election day vote centers were located in areas where election day voting was less likely while no vote centers were at sites where voters typically vote on Election Day, thus creating a disadvantage to voters known to vote on Election Day. The ability of election officials to accurately administer precinct voting is significantly enhanced when compared to vote centers: such things as the ability to pre-order the quantity of ballots needed for a finite number of voters would eliminate myriad issues of polling locations running out of ballots, jamming of printers required for ‘ballot on demand’ at vote centers, not to mention the strengthened accuracy of election results when precinct officials are able to reconcile the voters to the ballots at the precinct prior to forwarding to the county and to conduct other statutory requirements such as ensuring that all tabulator tapes are signed, and other safeguards are followed. The vast number of errors, irregularities and ‘glitches’ are largely avoided when voting and tabulating occurs in precincts.

By contrast, large vote centers typically rely on countywide or jurisdiction-wide electronic pollbooks that allow any eligible voter to check in at any location, greatly increasing the volume of voters and transactions that each location must handle.

Precinct-scale operations, when properly staffed and trained, enable more meaningful observation and reconciliation: poll workers can track check-ins against expected turnout, monitor provisional and challenged ballots, and reconcile the pollbook with ballots cast in a transparent close-of-polls procedure. Any resilient architecture must therefore decentralize not only tabulation, but also eligibility verification, keeping these functions within a scope where real scrutiny is still possible.

Where the “convenience” turnout story falls short

Proponents of vote centers often argue that allowing voters to cast a ballot anywhere in the county will increase turnout by making voting more convenient. The empirical record so far is far more mixed. Studies of jurisdictions that moved from precinct-based voting to vote centers find turnout increases in some places and decreases in others, with effects that vary by county type and population. In several cases, any convenience benefit appears to accrue mainly to already-consistent voters, while less-frequent voters and those facing transportation barriers do not see comparable gains.

A broader body of research on polling-place consolidation and distance to the polls shows consistent turnout risks. The Voting Rights Lab’s review of consolidation experiments concludes that closing or consolidating polling places tends to suppress turnout, particularly among Black and Latino voters, and that other methods such as vote-by-mail or early voting only partially offset these losses. Studies of distance and travel time similarly find that increasing the distance to a polling location, or forcing voters to adjust to new locations, reduces participation rates in general elections. In rural areas and communities with fewer transportation options, the shift from many local precincts to fewer centralized sites can be especially damaging.

From a risk-benefit perspective, this record undermines the simple narrative that vote centers are a net turnout booster. At best, they appear turnout-neutral on average—helping some groups while hurting others—and at worst they function as a convenience upgrade for reliable voters while raising participation costs for less-resourced communities. When weighed against the security and transparency risks of concentrating voting and tabulation into fewer, more complex sites, the case that vote centers are worth the tradeoff becomes much harder to sustain.

Re-centering precinct voting and hand-marked paper ballots

The most promising path toward a more robust and comprehensible election system is not further centralization and technical complexity, but a hybrid architecture that restores precinct-level resilience while standardizing voting on pre-printed, secured hand-marked, optically scanned paper ballots as the primary record of voter choices.

Hand-marked paper as the backbone of honest elections

Technical panels and election-security researchers increasingly view hand-marked paper ballots, scanned and securely retained, as the cornerstone of a trustworthy system.

While ballot-marking devices remain essential for accessibility for the disabled, treating pre-printed hand-marked paper as the default method of voting with BMDs or DREs used only as an accommodation to those who require it reduces the surface area of complex machinery and software that can affect large numbers of ballots and votes.

Precinct-level scanning with limited centralization

A hybrid model would retain some centralized functions while decentralizing the core of voting and initial tabulation:

This structure does not eliminate some need for central aggregation, but it ensures that central tabulators aggregate many separately verifiable, precinct-level results on a smaller scale rather than functioning as the locus of counting.

The cost myth of highly centralized vote centers

Proponents of vote centers often justify consolidation by citing reduced costs: fewer locations, fewer poll workers, and fewer pieces of equipment. However, these claims typically assume jurisdictions will invest in sophisticated electronic pollbooks and high-capacity voting devices, which are expensive to purchase, maintain, and regularly upgrade. Studies of voting-equipment costs indicate that replacing or expanding fleets of complex electronic machines, especially those used as universal ballot-marking devices, can require substantial capital and ongoing expenditures for licensing, maintenance, and specialized support.

By contrast, hand-marked paper ballots, paired with precinct-based optical scanners, tend to be cheaper per voter over time, particularly when the full life-cycle costs of complex equipment are included. Paper, outfitted with security features, is inexpensive; scanners can have long service lives; and operational procedures are simpler to train and support than those needed for large, fully electronic vote centers. The apparent cost savings of consolidation can therefore mask a shift toward more technologically intensive—and ultimately more expensive—systems that demand constant attention from specialists.

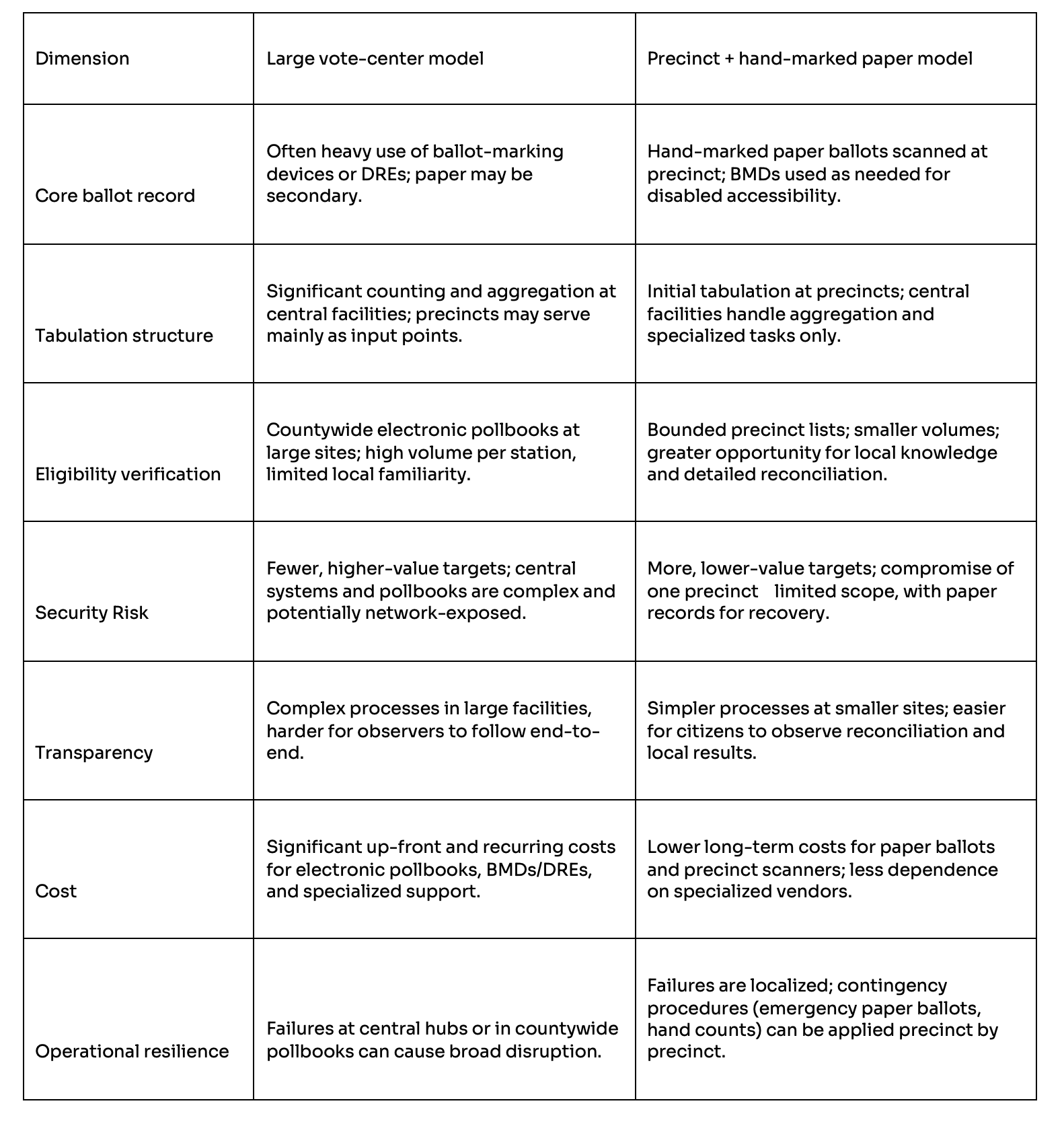

Comparing models: vote centers vs. precinct + hand-marked paper-Structural tradeoffs in election architecture

Conclusion: Reducing reliance on central lynch pins

Central tabulation centers and large vote centers are, by design, the choke points of contemporary election systems, making them the logical place to focus both security efforts and policy concern. Evidence from 2020 in Georgia, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Arizona shows that, despite unprecedented stress and controversy, the certified presidential outcomes were not overturned through recounts, audits, or litigation, but that fact reflects the narrow standards and institutional limits of post-election remedies as much as it reflects the quality of central-count processes themselves.

A more durable and democratic architecture is available. By restoring precinct-level resilience, centering hand-marked paper ballots, and limiting the power and complexity of central tabulation centers and large vote-center operations, election administrators can reduce both the probability and the consequences of failure, while making elections more transparent and comprehensible to the citizens whose consent they must secure.